Fela Anikulapo Kuti, a legendary and trailblazing Nigerian musician, made waves for his nonconformity, principles, and radical temperament. He was dubbed the “Father of Afrobeat” and achieved worldwide acclaim for his music. He was also a human rights activist and Pan-Africanist who had a lot of problems with Nigerian politicians and the law since he was not afraid to speak his thoughts, whether it was through music or spontaneous discussions.

Kuti was a true artist. His record covers, which attacked political oppression, corruption, police brutality, and other issues, reflected his social and political ideas. Like his music, it was impossible to overlook his album covers.

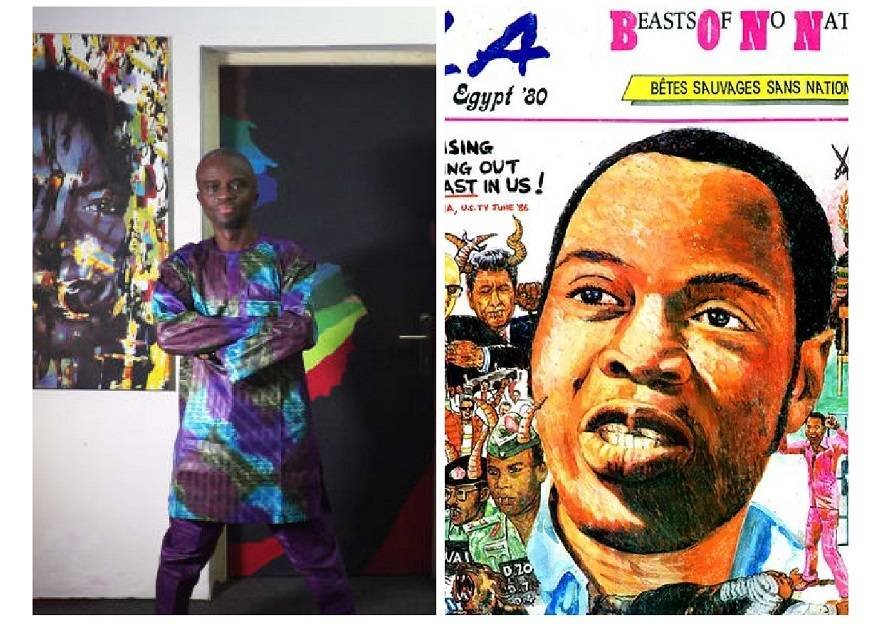

The majority of these memorable record covers were created by Lemi Ghariokwu. Many of the singer’s songs, including “Zombie,” “No Bread,” and “Beast of No Nation,” were designed by the Nigerian designer.

“While he was living, I designed 26 covers and developed a movement of art and music,” Ghariokwu, now in his mid-60s, told CNN.

When the artist was five years old, he began drawing with a broomstick on the sand streets of Lagos about cars that passed by. His father wanted him to study engineering, but he preferred the arts. So, after being influenced by the works of British artist Roger Dean, he began practicing art seriously after finishing primary school.

Read Also:

This Cameroonian Physician Finds New Approach In Treatment Of Cancer Using Cheap Smartphones

Following that, Ghariokwu formed a bond with musician Sonny Okosun. When Okosun was asked to do a TV interview, Ghariokwu accompanied him and sketched the host. He was shortly invited to draw on live television by the studio. Ghariokwu told the Guardian, “I always made sure I was finished by the time the performance ended so the public could witness [the finished result].”

Ghariokwu ultimately met Kuti when he was 18 years old, courtesy to journalist Babatunde Harrison, who was enthralled by a Bruce Lee painting Ghariokwu created for his neighborhood bar. Harrison asked Ghariokwu to sketch an image of Kuti before taking him to meet the Afrobeat maestro to determine if he deserved to meet him. When Ghariokwu eventually got to meet Harrison and Kuti at his communal compound, known as the Kalakuta Republic, he created the portrait, which drew their attention.

His family, band members, recording studio, and others were all housed in the communal property. Ghariokwu and Kuti hit it off right away. Because of their views on social issues and beliefs in spiritualism and Black empowerment, they became like family. Ghariokwu was already inspired by the Black Panthers in the United States at the time, identifying them as heroes. Civil rights leaders and musicians like Miriam Makeba were other favorites of his.

Instead of going to university, Kuti recommended the young artist buy books and read more about politics, history, spirituality, and art. And that’s exactly what Ghariokwu did. “His main argument was that if you go through that miseducation system, you would lose your uniqueness and personality,” Ghariokwu told CNN.

Ghariokwu spent four years in Kalakuta, following Kuti while he worked on new songs. After that, he’ll focus on visualizing the soul of his song. Some police officials raided Kuti’s Kalakuta property in November 1974 and arrested him. Police stormed his residence in the guise of looking for a young woman who had been falsely accused of being kidnapped by Kuti. The officers are said to have thrashed Kuti severely.

Ghariokwu recalls meeting him at the hospital, where he had a shattered skull that required 17 stitches. “However, he stated that he intended to write a song that was directly critical of the cops. That’s when he decided to take on the role of directly opposing the establishment.”

Alagbon Close, the title track of a Kuti album that featured Ghariokwu’s artwork for the first time, was inspired by that song denouncing the cops. Ghariokwu told VF, “This was my first ever chance.” “I designed my cover art, and it’s instructive in the sense that it foreshadowed what I’d do on his covers in the future.” My cover image was abstract, and it didn’t directly relate to the lyrics.”

“It was the first time in Nigeria that people raved about the music when the record was launched, and they also raved about the album cover art,” he continued. “That was the start of the album cover art dynasty.”

During this time, Kuti became a vocal critic of Nigeria’s military authorities, and his Kalakuta Republic home was burned down by 1,000 soldiers shortly after the release of his political album Zombie in 1976. “I was 22 at the time. Ghariokwu described the encounter as “terrifying crap,” adding that it began to impact his friendship with the famed musician.

Worse, he got into a disagreement with Kuti about the cover art for 1977’s Sorrow Tears and Blood. “I showed him the artwork, and he [glared] and complained that his burning Republic wasn’t included. Why would I depict a burning house if it happened a year ago? ‘Check your mind, your mind is weak,’ he poked my chest. In an interview with the Guardian, Ghariokwu said, “I drove away crying, I was really upset.”

Ghariokwu’s art and popularity did not perish after he ceased working with Kuti after only four years. He went on to produce thousands of covers for other artists and even founded the Afro Art Beat movement. Since then, he’s designed over 2,000 album covers and shown his work in Lagos, New York, and London.

“I work with radicals daily.” Their warrior souls fascinate me. He told CNN that all of his heroes are “warrior spirits.” “I’m not a warrior spirit,” says the narrator. I’m a Darwinian… As an evolutionary, I feel we need to properly package and work on things. It will now increase with time.”