When Martin Luther King Jr delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington 57 years ago, around 250,000 people attended the event, including prominent figures such James Baldwin, Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier.

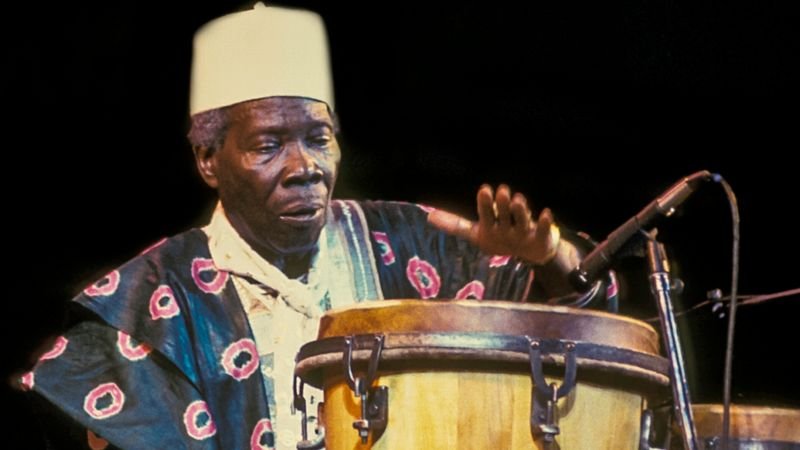

Among the guests was perhaps a slightly more unexpected figure, Nigerian drummer Babatunde Olatunji.

Born in 1927 to a Yoruba family in Lagos state, Olatunji won a scholarship to study at Morehouse College in Atlanta in 1950.

He became a pioneering drummer, releasing 17 studio albums, including his 1959 debut Drums of Passion, widely credited with helping to introduce the West to “world music”.

Despite Olatunji’s enduring musical legacy, which includes a Grammy nomination and compositions for Broadway and Hollywood, his civil rights advocacy is less well known.

“He was committed to social activism throughout his life,” says Robert Atkinson, who collaborated with Olatunji on his autobiography, The Beat of My Drum, which was published in 2005, two years after his death.

As a Morehouse student, Olatunji encountered ignorance and stereotypes about Africa and strove to educate his fellow students about the continent’s music and cultural traditions.

He started playing African music at university social gatherings and gave drumming demonstrations at both black and white churches across Atlanta.

“Baba sparked a deep sense of pride among African Americans by strongly promoting images of African culture, which in a subtle but significant way, helped set in motion the currents of the early civil rights movement,” Atkinson says.

At a time of state-sanctioned racial segregation in the US, Olatunji quickly became acutely aware of racism, and began organizing students to challenge so-called “Jim Crow” laws in the south.

In 1952, three years before Rosa Parks helped spark the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama, Olatunji staged his own protests on public buses in the south.

On one occasion, he and a group of students boarded a racially segregated bus in Atlanta wearing traditional African clothes and were allowed to sit anywhere they wanted, because they were not identified as African Americans, who had to sit at the back.

The next day, they boarded the same bus in their Western clothing and refused to sit in the back when ordered to do so by the bus driver. Olatunji and his friends continued to challenge segregation in this way jail threat.

“We started the protest quietly,” Olatunji later recalled of the incident. “We were part and parcel of the struggle for freedom in the early 1950s.”

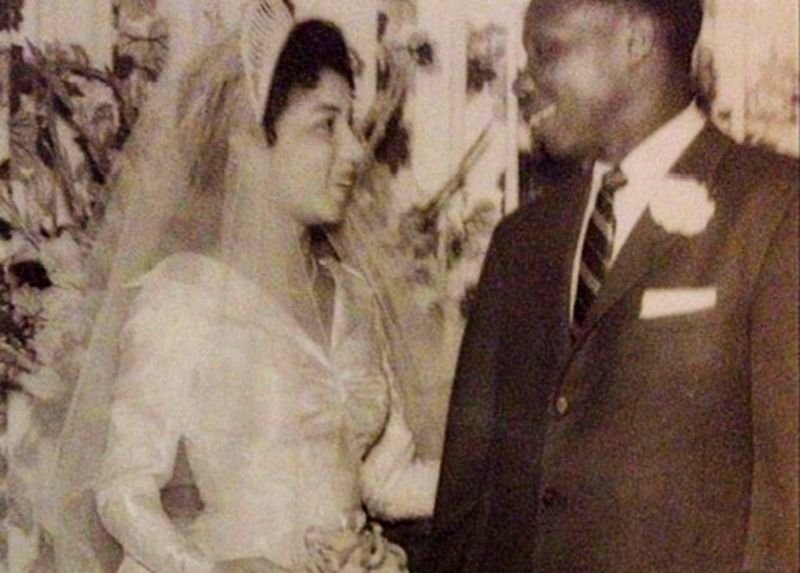

Olatunji’s widow, 89-year-old Iyafin Ammiebelle Olatunji, told the BBC that he was called in to “ease the tensions in various communities”, such as during the aftermath in 1965 of deadly riots in the predominately black neighbourhood of Watts in Los Angeles.

“He saw himself as a pan-Africanist who always reached out to unify Africans and African Americans,” she said.

Olatunji became a president of the Morehouse student body, which led to him meeting many early civil rights leaders in the 1950s, including Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X.

His involvement in the US civil rights movement was strongly inspired by the wave of anti-colonial resistance movements sweeping across Africa during the 1950s and 1960s, of which he was a part.

In 1958, he travelled to Accra, Ghana to attend the All African People’s Conference organized by Ghana’s independence leader Kwame Nkrumah.

The conference brought together leading independence figures and delegates from 28 African countries and colonies to strategize their opposition to European colonization.

In 1957, Martin Luther King Jr was invited to Ghana’s first independence day celebrations, and met Nkrumah. The meeting had a profound effect on King, who drew inspiration from Ghana’s anti-colonial struggle.

In the 1962 American Negro Leadership Conference, King drew a more direct comparison between colonialism in Africa and American segregation, saying the two were “nearly synonymous… because their common end is economic exploitation, political domination, and the debasing of human personality”.

Meanwhile, King’s counterpart Malcolm X embraced the anti-colonial uprising of the Mau Mau movement in Kenya, and believed that adopting some of its tactics could help eradicate the Ku Klux Klan in the US.

He also met several African leaders to discuss the African-American civil rights struggle and received support in particular from Tanzania’s founding President Julius Nyerere. In 1964, Nyerere helped Malcolm X convince African leaders to pass a resolution at the Organization of African Unity (OAU) summit imploring the US to eliminate racial discrimination.

Malcolm X also interacted with Africans in the US, where he met Olatunji, who drummed at civil rights rallies at his request.

“He had a close relationship with both Martin Luther King and Malcom X,” Atkinson says.

“Baba was a bridge between the two approaches of the time: King’s was non-violent and Malcolm’s not so much sometimes.”

According to Olatunji’s eldest daughter, Modupe, she added: “His work ethic was still evident until the end of his life.”

Their father died in 2003 one day before his 76th birthday. His legacy of music and activism continues to inspire successive generations, particularly contemporary Africans in America who draw on his example of bridging the continent with its diaspora.

“We have picked up the baton from a previous generation and we’re continuing to run the race that they started,” says Ms Tometi of BLM.

Olatunji’s biographer adds: “This is a perfect time for people to know about Baba. These demonstrations for justice are such a new and greater uprising of what he was part of 60 years ago.”