On a sweltering August night in 2014, DeRay Mckesson sat on his couch in Minneapolis, scrolling through Twitter. What he saw would irrevocably alter the trajectory of his life. A teenager, Michael Brown, lay dead in the street in Ferguson, Missouri, shot by a police officer, his body left uncovered for hours.

The images sparked something visceral in the 29-year-old school administrator. Within hours, Mckesson made a decision that baffled colleagues and friends: he packed a bag, got in his car, and drove nine hours to a city he had never visited, towards a situation most people were desperately fleeing.

That spontaneous journey transformed a former teacher into one of the most recognisable faces of the twenty-first century civil rights movement. Almost a decade later, Mckesson remains a singular and sometimes controversial figure in the ongoing struggle for racial justice, channelling the fury of the streets into policy proposals, podcasts, and prose.

Born in West Baltimore in 1985, Mckesson’s early life bore little indication of the prominence to come. Raised primarily by his father, Calvin, and his great-grandmother after his mother left when he was three, he grew up immersed in a community of recovery; his father was a lifelong Narcotics Anonymous attendee.

The family eventually moved to the suburb of Catonsville, where Mckesson flourished, serving as class president and cutting his teeth as a community organiser with a youth grant-making organisation. He became the first person in his family to attend a selective liberal arts college, graduating from Bowdoin College in Maine in 2007 with a degree in government and legal studies.

His career began not in activism but in the classroom. Through Teach for America, Mckesson taught elementary school in New York City before moving into human resources roles within the school systems of Baltimore and Minneapolis. By 2014, he was a senior director making a six-figure salary, comfortable but, as he later described, with a limited imagination for what his life could become. The events in Ferguson expanded that imagination dramatically.

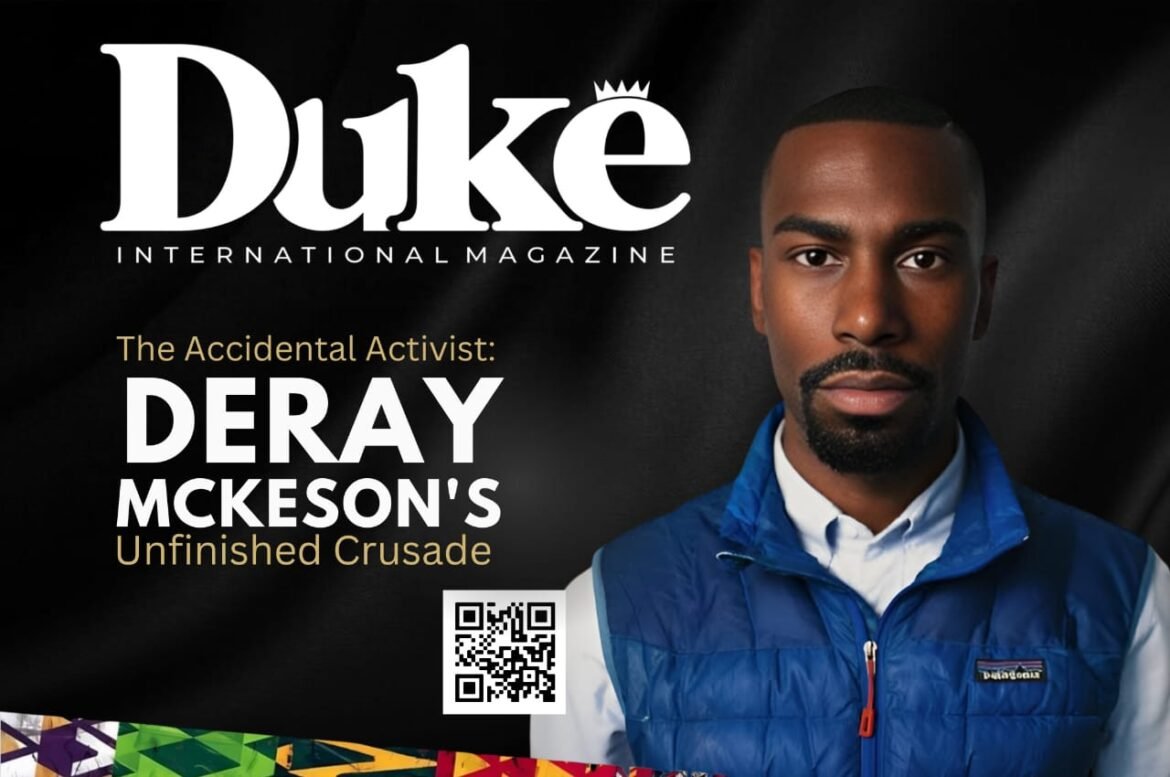

What Mckesson intended as a weekend visit to witness the protests became a calling. He began spending every weekend and vacation day in St Louis, documenting the unrest on social media with a calm, real-time urgency that attracted hundreds of thousands of followers. His signature blue Patagonia vest became an unlikely symbol of the movement, a sartorial trademark in the sea of protesters . In March 2015, he made the rupture official, tweeting that he had quit his job and moved to Missouri.

Alongside fellow activists Johnetta Elzie, Brittany Packnett Cunningham, and data scientist Samuel Sinyangwe, Mckesson sought to translate street-level anger into tangible change. The group launched Mapping Police Violence, a database cataloguing killings by law enforcement, followed by Campaign Zero, a ten-point policy platform designed to end police brutality through legislative reform.

The initiative proposed concrete measures: ending broken-windows policing, establishing community oversight, and limiting the use of force. Their work earned them meetings with President Barack Obama at the White House and praise from figures as varied as Oprah Winfrey and Hillary Clinton, who had challenged protesters to present a specific vision and plan.

Yet the very visibility that made Mckesson effective also attracted scrutiny. His rapid ascent to prominence, complete with magazine covers, a spot on Fortune’s World’s Greatest Leaders list, and a portrait in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, led some to question whether the movement was replicating an old pattern: the media anointing a male spokesperson while the labour of black women organisers remained less celebrated.

Tensions within Campaign Zero eventually frayed the founding partnership. Elzie departed in 2016, feeling her contributions as a black woman were being diminished.

Mckesson’s 2016 bid for mayor of his hometown, Baltimore, ended in a distant sixth place in the Democratic primary, a result his critics saw as evidence of a disconnect between his online fame and on-the-ground political reality. His association with Teach for America and support for charter schools also drew fire from public education advocates who viewed the organisation as a destabilising force in communities of colour.

Through it all, Mckesson has continued to evolve. His 2018 memoir, On the Other Side of Freedom: The Case for Hope, was a deeply personal work that explored not only his political awakening but also the pain of his mother’s abandonment and his experience as a gay man, topics he had long held close.

The book made a nuanced distinction between optimism and the harder craft of hope, a belief that collective action could forge a better tomorrow.

Today, Mckesson hosts Pod Save the People, a weekly discussion of news, culture, and social justice that reaches a broad audience, and he serves on the board of trustees for the Council on Criminal Justice. He remains a resident of Baltimore, the city that shaped him, and has not ruled out another run for office.

His journey from human resources official to full-time organiser, from the streets of Ferguson to the corridors of power, illustrates the many fronts on which the battle for racial equity is now fought. For Mckesson, the work is far from finished; it has simply moved indoors.